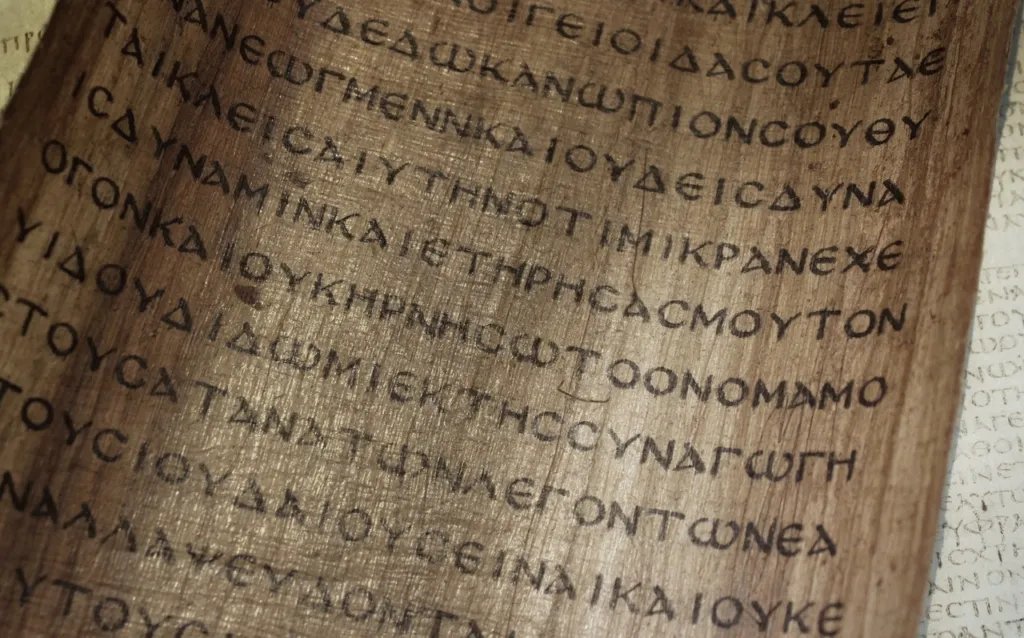

The early achievements of Greek literature are evident in two epic poems, Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey (c. eighth century BCE). The Iliad relates the story of the Trojan War fought between Troy and Greece, focusing primarily on Achilles, the mightiest Greek warrior. Along with powerful descriptions of battles and deaths, the epic contains deep emotional content, particularly in the grief Achilles feels after Hector, the Trojan king’s eldest son, kills his friend Patroclus. Struggling with his loss, Achilles avenges Patroclus’s death by stabbing Hector through the neck with a spear. Hector pleads with him to return his dead body to his family for burial rather than to leave him on the battlefield, but Achilles furiously responds,

“No more entreating of me, you dog, by knees or parents. I wish only that my spirit and fury would drive me

to hack your meat away and eat it raw for the things that you have done to me. So there is no one who can hold the dogs off

from your head, not if they bring here and set before me ten times and twenty times the ransom, and promise more in addition.”

Achilles eventually relents, but the power of his emotions raises a story of battle into a deep exploration of human suffering and forgiveness. The Odyssey, a sequel to The Iliad, narrates the trials of the Greek hero Odysseus during his ten-year journey home after the Trojan War. Unlike The Iliad, which focuses on the trials of war, The Odyssey includes many elements of an adventure story. In part it depicts the challenges faced by Odysseus’s wife Penelope and son Telemachus, who must contend with the many dissolute suitors wooing her. Odysseus’s adventures during this time consistently hinder him from returning home. Captured by the Cyclops Polyphemos, he and his men blind the monster to escape; they stay on the island of Circe, a sorceress, and Odysseus travels to the land of the dead. Eventually, after a shipwreck drowns all but Odysseus, Calypso holds him captive for seven years, hoping to marry him. Only when the gods intervene is Odysseus freed, eventually finding his way home and slaughtering Penelope’s suitors. With their stories of heroism and the challenges of defending one’s nation and family, The Iliad and The Odyssey testify to the emotional appeal of the epic tradition as well as to its broad scope of action and setting. (For a discussion of literary epics, see pp. 118–20.)

As Homer developed the epic tradition, Hesiod innovated in the traditions of didactic poetry, which teaches readers important lessons. His most famous texts, Theogony and Works and Days, date from around the eighth century BCE. Theogony presents the history of the gods in the Greek pantheon, including stories of Zeus, Hera, Aphrodite, Gaia, and Demeter.

He presents their origins and their interrelationships, starting with the creation of the Earth: “First of all, Chaos came into existence; thereafter, however, / Broad-bosomed earth took form, the forever immovable seat of / All of the deathless gods who inhabit the heights of Olympus” (lines 112–14). Hesiod dedicates Works and Days to his brother Perses, advising him about agriculture. In some ways, this publication resembles modern farmers’ almanacs, providing advice such as “Every year when you hear the shrill din of the cranes from the clouds, take / Note, for it signals the season to plow, indicating the rainy / Wintertime, gnawing the heart of the man who possesses no oxen” (lines 441–43). This work also advises Perses to accept the lot of humans through references to stories of the gods, such as the legend of Pandora and the suffering resulting from her curiosity. Together, Hesiod and Homer established key foundations for Western literature through their interest in epics, didactic poetry, and the Greek pantheon.

Writing circa 600 BCE, Sappho lyrically captures the delights and jealousies of love in her verse. Her poems sing of passionate feelings for both men and women, and due to the romantic feelings expressed for women in some poems, the term Sapphic describes lesbian relationships. Fragment 1 of her work is a rare complete poem, for most of her writings have been lost. It depicts Sappho (the speaker) beseeching Aphrodite, the goddess of love, for help with heartbreak. Aphrodite, speaking of Sappho’s lover, reassures her that

If she balks, I promise, soon she’ll chase,

If she’s turned from gifts, now she’ll give them.

And if she does not love you, she will love,

Helpless, she will love.

(lines 21–24)

Sappho’s writing, direct yet passionate, captures love’s contradictions and longing, as evident in her ability to articulate deep feelings through Aphrodite’s words. With lines like “My tongue sticks to my dry mouth, / Thin fire spreads beneath my skin” (fragment 20, lines 9–10), she captures the physicality of sexual desire.

Pindar, also a lyric poet, is remembered for his victory odes for athletic competitions, which appear in four collections respectively named after the Olympian, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games. These odes praise the victors in competitions such as wrestling, boxing, and horse races, while also addressing such subjects as the role of the gods in human success and the hard work necessary for victory. In Olympian IV (c. 452 BCE), Pindar acknowledges the dedication and goodness of a chariot race’s winner:

For I praise him, ready indeed to train horses,

Glad to entertain all strangers,

With his pure heart turned

To Quiet who loves his city.

With no lie shall I stain the saying:

“Trial is the test of men.”

(lines 18–22, numbering

provided by translator)

Pindar’s attention to the effort involved in success speaks to the values celebrated in his poems. It is not enough to win, for victors must demonstrate goodness in their whole person. (For further discussion of Pindaric odes, see pp. 123–24.)

Classical Greek drama has profoundly affected European and American theater. The playwrights Aristophanes, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides wrote plays that define the contours of comedy and tragedy. Aristophanes’s comic plays include The Frogs, The Clouds, and Lysistrata (c. 411 BCE), which tells of its title character’s attempts to end the Peloponnesian War by convincing Greek women not to have sex with their husbands, hoping that their boycott will force men to choose peace. Among the tragedians, Aeschylus is known best for his plays The Persians and Agamemnon. Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex (c. 429 BCE) tells the story of King Oedipus, who unknowingly kills his father and marries his mother, and the tragic events that ensue. Equal disaster comes to pass in Antigone (c. 441 BCE), in which King Creon demands that the body of Antigone’s brother Polyneices, who lost his life in battle, be denied burial. This decision catalyzes a series of events resulting in the death of the heroine Antigone as well as the deaths of the king’s son and wife. Few Greek tragedies inspire such horror as Euripides’s Medea (c. 431 BCE), in which Medea’s husband Jason leaves her for another woman, Glauce. In anger, she kills Glauce by sending poisoned golden robes, and in irrational fury she also murders her two children, taking their bodies with her and leaving Jason without even the solace of burying them. She explains her reasons to Jason, expressing her hatred for him one last time:

MEDEA … You, as you deserve,

Shall die an unheroic death, your head shattered

By a timber from the Argo’s hull. Thus wretchedly

Your fate shall end the story of your love for me.

JASON: The curse of children’s blood be on you!

Avenging Justice blast your being!

MEDEA: What god will hear your imprecation,

Oath-breaker, guest-deceiver, liar?

Medea’s cruel desire for revenge blinds her to the horror of killing her children. A fascinating character, she behaves horrifically, yet she completes her plans with little sense that the gods frown on her actions. Many Greek tragedies resist endings that might imply an overarching justice guides the universe, interrogating instead humanity’s limited understanding of the world.

Classical Greece’s rich theatrical world also includes the beginnings of literary criticism and philosophy. In his Poetics (c. 335 BCE), Aristotle discusses tragedy in depth, offering definitions of the genre and theorizing about its effects. His Rhetoric focuses on the art of persuasion. (For more on Aristotle and tragedy, see pp. 164–65; for Aristotle and rhetoric, see pp. 249–50.) Aristotle’s mentor Plato wrote a series of dialogues between his teacher Socrates and a variety of interlocutors on issues related to morality and ethics. These exchanges feature Socrates asking a series of questions to expose the weaknesses in others’ thinking. In the dialogue “Crito,” Socrates awaits his execution in jail when Crito, who wants to liberate Socrates by bribing the guards, visits. Socrates engages Crito in a discussion regarding the ethics of such an escape, leading Crito to recognize that Socrates must live by the laws of Athens. The Socratic method of questioning established a pedagogical approach to critical thinking that has lasted for centuries. It is, however, only through the writings of others, such as Plato’s dialogues, that Socrates’s ideas remain. The impact of these and other writers from the pre-classical and classical Greek era on Western literature cannot be overstated, for they established foundational principles of poetry, drama, and philosophy that remain in effect today, and were particularly influential on the many masterful Roman writers in the centuries that followed, including Virgil, Ovid, and Seneca.