Modernism is a term encompassing numerous movements characterizing international developments in literature, music, and the graphic and plastic arts from the late nineteenth century onward. Most commentators consider literary Modernism’s typifying manifestations in English to have appeared between 1890 and 1930. Among the authors most frequently cited are Joseph Conrad, T. S. Eliot, William Faulkner, Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, D. H. “Lawrence, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Virginia Woolf, and W. B. Yeats; European writers associated with Modernism include Bertolt Brecht, Andre Gide, Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Marcel Proust, and Rainer Maria Rilke, while Charles Baudelaire, Gustav Flaubert, and Arthur Rimbaud are regarded as three of its principal progenitors. The experimental qualities thought of as essentially Modernist are found in the writings of many of the above; others are more traditional in their stylistic and narrative practices. All, however, respond acutely to the radical shifts in the structures of thought and belief that were brought about in the fields of religion, philosophy, and psychology by the works of Sir James Frazer, Charles Darwin, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and others. The moral cataclysm of the First World War accentuated the senses of general cultural catastrophe and individual spiritual crisis apparent in the writings of novelists and poets already sensitive to such disruptions in the humanist tradition. Pound’s Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), Eliot’s The *Waste Land (1922), Woolf s Jacob’s Room (1922), and Joyce’s “Ulysses (1922) are among the works which indicate the breach with the conventions of rational exposition and stylistic decorum in the immediate post-war period.

Literary Criticism

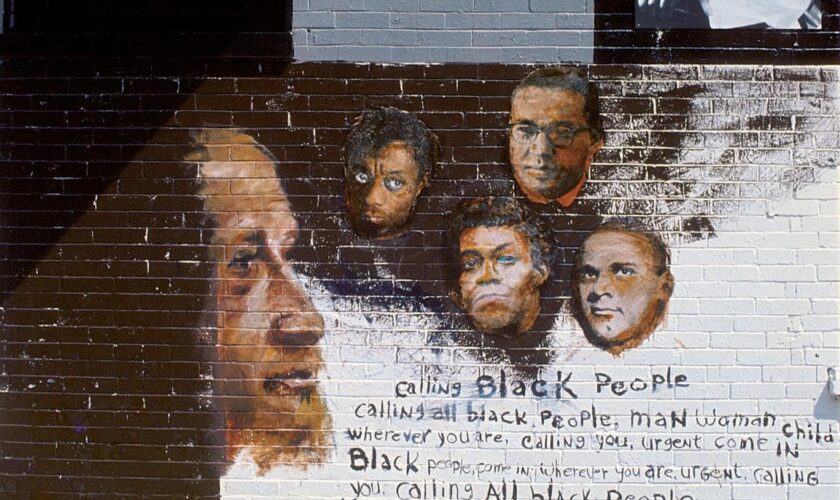

African American poetry began in the lyrics attached to field hollers, ring shouts, rudimentary work songs, and songs of familial entertainment in the early colonies of the Americasin the North, South, and the Caribbean. These musical verses were characterized by insistent call and and response patterns, complex African and neo-African polyrhythms, the adaptation of European rhyme as a means of complexifying rhythm, and the transformation and incorporation of European harmonies into distinctive chords, which were the forerunners of chords and lyrics that characterize the African American lyrical poetic genres of gospel, blues, jazz, the mast, the chanted sermon, rhythm and blues, soul, rap, and contemporary polyphonic poetry. The polyphonic poetry of such twentieth-century poets as Derek Walcott, E. Kamau Brathwaite, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Robert Hayden, Ishmael Reed, Countee Cullen, Lorna Goodison, Langston Hughes, Jay Wright, Rita Dove, Ai, and Etheridge Knight all reconstrue African rhythmic complexity with creative and personally distinctive transformations of Euro-American, African American, Caribbean, Latin American, and Asian styles and motifs. The designation African American, while an appropriate term for cultural identification, is yet another incomplete summary of a black people more accurately called the African-British-European-Native American-Asian peoples of the Americas.

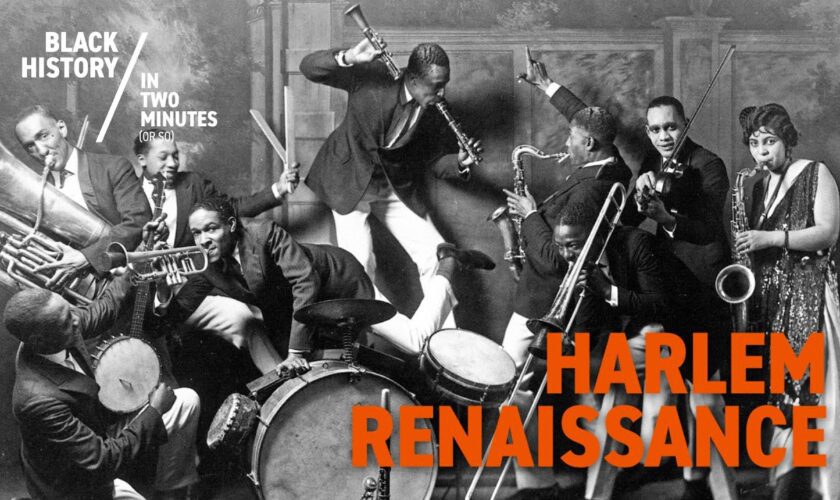

The term normally used to describe the upsurge of black American writing in the 19205 and 19305. Though sometimes seen as a movement, it is better regarded as the more or less contemporary emergence of a number of writers who together make up the first modern generation of black American writers, a generation whose work, while often protesting about dispossession, poverty, and racial prejudice, is most significant for its articulation of a positive sense of black identity and its attempts to promote black consciousness. Harlem, viewed as a cultural matrix for blacks, provided a central focus for the activities of several of the writers who contributed to the Renaissance, or Awakening as it is sometimes also called, but others lived all or most of their lives elsewhere. Although there had been numerous earlier works that gave voice to the predicament of Americans of African descent, among them Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), which is the best-known ‘literary’ example of the genre of slave narrative, Charles W.

Chesnutt’s The Conjure Man (1899), and James Weldon Johnson’s Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man (1912), a work which is sometimes seen as a forerunner of the Awakening, the Renaissance is generally viewed as a major step forward. Figures instrumental in its formation included the sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, best known for his The Souls of Black Folks (1903), who rejected the integrationist approach of his famous contemporary Booker T. Washington, and the Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, whose United Negro Improvement Association promoted an awareness of African origins and the possibility of an actual repatriation to Africa in Harlem in the 19205. Other historical factors which contributed to the growth of a sense of distinctive racial identity and the emergence of an autonomous black literature in the 19205 included the racism from which many black Americans suffered when they served alongside their white compatriots in the First World War, the northward migration of blacks from the rural South, and the difficulties such newcomers experienced in adjusting to urban situations.

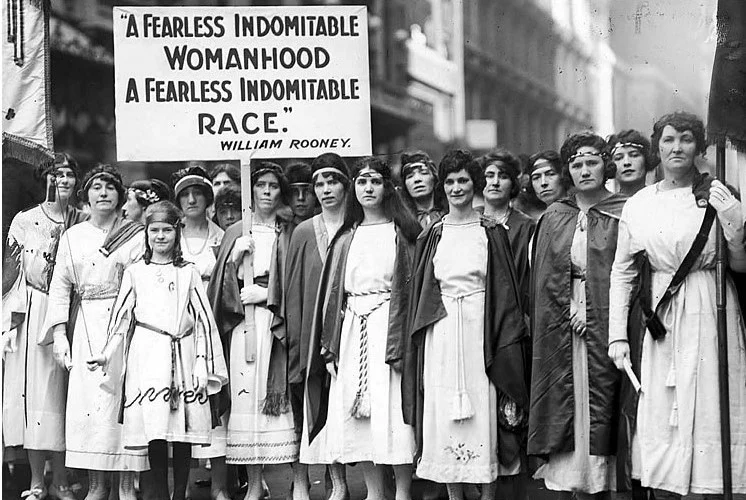

In 1968 the women’s liberation group New York Radical Women staged public demonstrations, including the Burial of Traditional Womanhood in January and the Miss America Protest in September. In June the group also published a short, typed journal titled Notes from the First Year. Alongside texts such as Anne Koedt’s “Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm” and Katie Amatniek’s “Funeral Oration for the Burial of Traditional Womanhood” was an essay by Shulamith Firestone called “Women’s Rights Movement in the u.s:’ Firestone rejected characterizations of the nineteenth-century woman activist as a “granite-faced spinster obsessed with a vote” (Firestone 1968: 1). Castigating those who spread “superficial, slanted, or downright false” information about feminist history, she identified its consequences: “To be called a feminist has become an insult, so much so that a young woman intellectual, often radical in every other area, will deny vehemently that she is a feminist, will be ashamed to identify in any way with the early women’s movement, calling it cop-out or reformist or demeaning it politically without knowing even the little that is circulated about it” (1). Firestone, like legions of activists before and after her, recommended education.

Drawing on the 1959 edition of historian Eleanor Flexner’s Century of Struggle, Firestone laid claim to the “dynamite revolutionary potential” present in the women’s movement from the beginning. He noted its connections with abolition and labor activism, and outlined its lessons for radical women of the time. Many of whom had become politically active in the New Left. She summarized: “1. Never compromise basic principles for political expediency. 2. Agitation for specific freedoms is worthless without the preliminary raising of consciousness necessary to utilize these freedoms fully. 3. Put your own interests first, then proceed to make alliances with other oppressed groups.

Demand a piece of that revolutionary pie before you put your life on the line” (Firestone 1968: 7 ). Asserting that “women’s rights were never won:’ she urged her contemporaries to continue the fight on economic, social, cultural, and legal grounds.

Firestone’s short essay not only sought to diminish the ignorance of activists of the 1960s about the heritage of US women but also recovered the experiences of earlier women as models and as cautionary tales to be applied in the present. She wrote in the informal idiom common to radical political movements of the 1960s, calling the antisuffrage groups of the early twentieth century “a female front for big money interests” (Firestone 1968: 3), noting the close ties between “the Black Struggle and the Feminine Struggle” (2), and bemoaning women’s routinized “shit jobs” (7) that fell far short of economic power. Rejecting the suppression of women’s history and the lies told by institutional authorities, Firestone’s essay led Notes from the First Year as an incendiary call to power through historical knowledge.

Firestone’s essay dramatically shows that history is not neutral or benign, and that arguments about what was significant in the past-or even about what happened-are embedded in the dynamics of the moment when the historical narrative is generated.

Appeals to the past are generated for rhetorical purposes, and the contexts of production and circulation of these appeals help to determine which aspects of the past are recovered and remembered. Whereas rhetorical scholarship is not equivalent to activist discourse, in that the audiences, purposes, and formal requirements differ markedly, it is still true that scholarly writing is rhetorical practice. Choices of subject, method, and conceptual framework are consequences of audiences, goals, and prior utterances. Firestone’s essay, with its fervent commitment to a usable past, illustrates a resonant historical connection: how we understand nineteenth-century feminism is intimately intertwined with mid-twentieth-century feminism. Furthermore, Firestone’s political lessons offer an analogical model for an evaluation of scholarship: What can we learn, what can we celebrate, and what can we do better? In this article, we argue that by attending to the past we sharpen our understanding of how we came to know and how we might know more, or better, or differently, in the future.

Around the beginning of the twentieth century, the predominant critical modes were biographical, historical, psychological, romantic, and impressionistic. Liberal critics such as Parrington and F. O. Matthiessen employed a historical approach to literature but Matthiessen insisted on addressing its aesthetic dimensions. This formalist disposition became intensified in both the New Criticism and the Chicago School. The term “The New Criticism” was coined as early as 1910 in a lecture of that title by Joel Spingarn who, influenced by Croce’s expressionist theory of art, advocated a creative and imaginative criticism which gave primacy to the aesthetic qualities of literature over historical, psychological, and moral considerations. Spingarn, however, was not directly related to the New Criticism that developed in subsequent decades. Some of the important features of the New Criticism originated in England during the 1920s in the work of T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, as well as in seminal studies by I. A. Richards and William Empson. Richards’ Principles of Literary Criticism (1924) advanced literarycritical notions such as irony, tension, and balance, as well as distinguishing between poetic and other uses of language. His Practical Criticism (1929), based on student analyses of poetry, emphasized the importance of “objective” and balanced close reading which was sensitive to the figurative language of literature. Richards’ student William Empson produced an influential work, Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), which was held up as a model of New Critical close reading.

Across the Atlantic, New Critical practices were also being pioneered by American critics, known as the Fugitives and the Southern Agrarians, who promoted the values of the Old South in reaction against the alleged dehumanization of science and echnology in the industrial North. Notable among these pioneers were John Crowe Ransom and Allen Tate, who developed some of the ideas of Eliot and Richards. Ransom edited the poetry magazine the Fugitive from 1922 to 1925 with a group of writers including Tate, Robert Penn Warren, and Donald Davidson. Other journals associated with the New

Criticism included the Southern Review, edited by Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks (1935–1942), the Kenyon Review, run by Ransom (1938–59), and the still extant Sewanee Review, edited by Tate and others. During the 1940s the New Criticism became institutionalized as the mainstream approach in academia, and its influence, while pervasively undermined since the 1950s, still persists. Some of the central documents of New Criticism were written by relatively late adherents: W. K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley’s essays “The Intentional Fallacy” (1946) and “The Affective Fallacy” (1949) (it is worth noting, in this context, the enormous influence of E. D. Hirsch’s book Validity in Interpretation, published in 1967, which equated a text’s meaning with its author’s intention); Austin Warren’s The Theory of Literature (1949); W. K. Wimsatt’s The Verbal Icon (1954); and Murray Krieger’s The New Apologists for Poetry (1956).

Throughout the eighteenth century, in the years leading up to the American Revolution, many colonists pondered issues related to independence and governance. Support for religious freedom played a role in the civic life of the colonies, and in the 1730s and 1740s a revival of religious faith known as the Great Awakening took hold. Jonathan Edwards, a Congregationalist minister, played a vital role in this movement, which deemphasized tradition and ritual in religion, focusing instead on helping believers to develop a personal connection with their faith: to feel emotionally attached to their beliefs rather than to experience them intellectually. In 1741 he delivered the sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” which outlines the misery of hell awaiting those who ignore God’s teaching. His sermon ends by summoning sinners to return to God while time remains to repent: “it is that natural men are held in the hand of God, over the pit of hell; they have deserved the fiery pit, and are already sentenced to it … ‹In short, they have no refuge, nothing to take hold of; all that preserves them every moment is the mere arbitrary will, and uncovenanted, unobliged forbearance of an incensed God” (156–57). In addition to the sermons of Edwards, George Whitefield, with his “Marks of a True Conversion” and “The Great Duty of Family Religion,” and Gilbert Tennent, with “The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry,” also participated in the Great Awakening, which likely influenced the coming American Revolution. The emphasis on personal, emotional experience rather than solely on churches’ official positions, as well as the recognition that all people face the same possibilities of salvation or damnation, may have primed Americans for more revolutionary ideas in politics and governance.

Throughout the remainder of the eighteenth century, American literature developed a character based less on faith and more on intellect. Benjamin Franklin, one of the most famous figures in the American Revolution, published his Poor Richard’s Almanack from 1733 through 1758, distributing useful information on such subjects as the weather, eclipses, and tides. More notably, Franklin’s almanacs instruct their readers with maxims, many of which remain in currency today: “He that goes far to marry, will either deceive or be deceived” (6), “Humility makes great men twice honourable” (7), and “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy wealthy and wise” (9). Years later he co-authored the Declaration of Independence (1776). Franklin’s Autobiography chronicles his rise from modest beginnings as the son of a candle maker, his training as a printer, and his success as a newspaper editor, leading to his position as a representative of the colonies. Franklin died before The Autobiography was completed, and so only events occurring prior to 1758 are depicted. An excellent example of autobiography, Franklin presents himself with refreshing candor.

A number of tracts criticizing colonial rule and promoting the establishment of the United States of America was published throughout the latter half of the eighteenth century. In Common Sense, published anonymously a few months before the start of the American Revolution in 1776, Thomas Paine articulates a “common sense” argument against British rule over America and for the development of an American government. Paine followed this publication with sixteen pamphlets collectively entitled The Crisis, published from 1776 through 1783. The Crisis inspired American readers, criticizing the tyranny of the English who, he believed, usurped powers that only God should have over men. He firmly believed that Americans were right to fight for independence.

Other authors focused on issues uniquely American in nature. J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur wrote Letters from an American Farmer (published 1782) prior to the American Revolution, while living on his farm, Pine Hill, in New York. In these letters, he discusses the animals, plants, and communities of America. For the most part, he idealizes the nation, discussing the multinational origins of Americans, their religious diversity, and the country’s role as a refuge for the poor and disenfranchised. Crèvecoeur advances the idea of America as a melting pot: “Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world” (70). Along with his positive representations of America, Crèvecoeur acknowledges the country’s weaknesses, condemning slavery and the failure of Americans to recognize the suffering of enslaved men and women. In his letters Crèvecoeur discerns a distinctly American culture in this fledgling nation.

Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) discusses the colony’s natural resources and influential social elements in America. Jefferson provides data about Virginia’s land and resources and discusses its people, religions, and laws, among other subjects. In his discussion of

slavery, Jefferson theorizes that, due to long-held prejudices and the effect of slavery, blacks and whites could not live together effectively in Virginia society. He therefore advocates relocating black men and women to Africa, after a period of education and work as slaves. Although Notes on the State of Virginia is among the most respected works of the eighteenth century, Jefferson’s position on slavery continues to create debate and criticism among current readers, especially in light of his relationship with his slave Sally Hemmings.

True independence and the establishment of American citizenship did not extend to African Americans or American Indians. Even so, a number of these Americans played important roles in this period of American literary history. Among the many ministers publishing sermons, Samson Occom, a Mohegan and Presbyterian minister, penned his “Sermon Preached at the Execution of Moses Paul” in 1772, the first publication in English by an indigenous writer. This sermon was delivered in Connecticut at the execution of Moses Paul, a Mohegan who killed a white man. Occom, a skilled rhetorician, published his sermon soon after its delivery, and it went through nearly twenty editions into the nineteenth century. Olaudah Equiano, born in what is now Nigeria circa 1745, was captured as a slave in 1756, sent to Barbados, and eventually sold to a Pennsylvania merchant. After buying his freedom in 1766, he left for England, later traveling to many other countries, but never returning to America. Equiano strongly supported abolition and lectured on the subject in England. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789) details his childhood in Africa and his horrid experiences as a slave, although recent evidence suggests that Equiano may have been born in South Carolina, making some of his story a fabrication (Carretta 96–105). Nonetheless, his vivid and dramatic descriptions in this book advanced the abolitionist cause. Equiano’s book represents a strong example of the slave narrative, a genre of autobiography common during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries recounting a slave’s life and mistreatment, including such later works as Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845) and Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861).

Of course, black Americans also wrote in genres other than slave narratives. The first published African-American poet, Phillis Wheatley was brought to Boston as a child in 1761 and sold to the wealthy Wheatley family, who educated her and encouraged her to write. In Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), she pens verse in several genres, including elegies written on famous figures, such as minister George Whitefield; reflections on God and faith; and patriotic lyrics supporting America. “To His Excellency, George Washington” (1775) resulted in a meeting between the two. She enjoyed fame for a short time, but her success did not last. Soon after Wheatley was emancipated, she married, but her family succumbed to poverty and she died when approximately thirty-one years old, having lost two children before her and a third soon after.

Other prominent American poets during the revolutionary period include Philip Freneau, who supported and fought in the American Revolution. His poems include “On the Emigration to America and Peopling the Western Country” (1779), “The Indian Burying Ground” (1788), and “On Mr. Paine’s Rights of Man” (1795). Joel Barlow’s The Vision of Columbus (1787) and the later revised edition of the work titled The Columbiad (1807) pay a patriotic tribute to America and brought him much literary respect. More recently, the poem’s critical reputation has fallen due to its rhetorical excesses. Of his poetry, “The Hasty Pudding” (1793) stands as his most lasting contribution to American literature.

Soon after American independence came the first American novels. During this period, the literacy rate improved, which increased readership for authors and booksellers. As the country was defining itself and its values, novels took up entertaining subjects that often intersected with social and political ideas. Recognized as the first American novel, William Hill Brown’s The Power of Sympathy (1791) explores with sentiment and emotion a romantic relationship discovered to be incestuous. The novel was intended to be engaging for readers but also instructive for young women in their conduct. Susanna Rowson’s Charlotte Temple (1794), the best-selling novel in America for approximately fifty years, tells of the seduction of Charlotte Temple, a teenager, who is impregnated but then deserted by her seducer. Rowson’s sentimental novel warns young women to protect their honor and to avoid being led astray. Hannah Webster Foster’s The Coquette: Or, the History of Eliza Wharton (1797) offers both entertainment and instruction for readers. This epistolary novel tells the story of Eliza Wharton, a young woman courted by two men: a clergyman and a libertine. After losing both men to marriage, she has an affair with Peter Sanford, the libertine, and finds herself pregnant. Alone and unmarried, Eliza gives birth, but her child dies, and Eliza dies soon after. Although the novel powerfully argues that feminine virtue is important above all else, the author also demonstrates great sympathy for Eliza and her struggles. The Coquette, like Charlotte Temple and The Power of Sympathy, is a sentimental novel, focusing on the realm of feelings rather than logic, and inviting readers to become emotionally invested in the characters’ lives. These are merely three of numerous American novels in the sentimental tradition, an eighteenth-century English literary tradition as well that enjoyed continuing popularity in nineteenth-century America.

The literary heritage of the United States begins with the many indigenous communities of the Americas, whose stories, chants, and prayers came down from generation to generation through oral performances, which changed with each teller. For many years, these stories remained within individual tribal communities, though some Native American oral texts were eventually transcribed. Many Native American creation stories share common features, such as the importance of the natural world, yet each story offers unique insights into the history and beliefs of its people. Several creation stories, including those of the Creek, the Iroquois, the Cherokee, and the Lakota, depict a cataclysmic flood, after which the current world, populated with people and animals, comes forth. Numerous stories, including those of the Navajo and Lakota, discuss the role of a trickster figure who participates in the world’s creation. North American creation stories unite the world of humanity with the natural world through such symbolically important animals as the wolf, turtle, and serpent.

Europeans traveling throughout the continent in voyages of discovery and acquisition produced the first major set of written texts coming from the Americas. The voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1492 inaugurated numerous exploratory trips authorized by Spain, Italy, England, and other European countries. Within fifty years after Columbus, Europeans had settled communities from the eastern coast of what is now Canada, along the eastern seaboard, and on throughout South America. Other explorers moved west through the interior of the continent. Throughout this period, explorers documented their experiences through a combination of travel journals and formal missives back to the governments sponsoring their travels. This literature of encounter records detailed information regarding the physical landscape, flora and fauna, and most importantly, the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Columbus’s letters to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella explain his early reactions to the New World, specifically to Hispaniola (comprised today of the Dominican Republic and Haiti). He describes the lush countryside ready for cultivation, as well as his plans to control the indigenous people if necessary. In his journal entry for October 15, 1492, Columbus notes that the Arawak Indians lack experience with fighting: “Your Highness will see from the seven whom I caused to be taken in order to carry them off that they may learn our language and return. However, when Your Highness so commands, they can all be carried off to Castile or held captive in the island itself, since with fifty men they would be all kept in subjection and forced to do whatever may be wished” (28). Columbus’s journals convey his interest in the place and its people, but also his indifference to the Indians’ welfare.

Other early explorers expressed a mix of emotions toward the New World. Bartolomé de las Casas, a Spaniard who traveled to America in 1502, criticized the ways the explorers treated indigenous peoples. For years Casas assisted in the settling of Hispaniola, work that included physical attacks on the Taino Indian community, supposedly undertaken as a defensive measure, although just as likely executed without provocation. Like other settlers, Casas conscripted slaves from among the indigenous people, taking their land and their liberty. After his ordination as a Roman Catholic priest in 1510, Casas realized that such violent measures for controlling the indigenous population were detrimental to the Indians and to his people. He released his slaves, and he also advocated for the rights of Native Americans, taking his argument to King Ferdinand. Although he initially failed to alter prevailing practices, he was appointed Protector of the Indians. In 1516 Casas presented to the King’s regents his “Memorial de Remedios para Las Indias,” which proposes methods for improving conditions in the West Indies, including ceasing the use of forced Indian labor and changing the economic system. Casas’s “Brevísima Relacíon de la Destruccíon de las Indias” (1542), a tract detailing the violent treatment of the indigenous people, initiated changes in Spain’s slavery laws. He also wrote Historia de las Indias, a three-volume work chronicling the history of the colonization of the West Indies, from 1492 through 1520.

La Relacíon de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, originally published in Spain in 1542, recounts the adventures of Cabeza de Vaca throughout the American South and Southwest. Cabeza de Vaca traveled in 1527 as part of a large exploration to Hispaniola and then on to the Florida coast, surviving shipwrecks and other catastrophes. His La Relacíon describes the years he roamed the region, including his imprisonment by the Karankawa, his work as a healer and merchant, and his life among indigenous groups, including the Pimas, Coahuiltecans, and Conchos. His descriptions of these tribes’ daily lives illuminate their customs and beliefs, including aspects of marriage, death rites, personal relationships, clothing, commerce, child-rearing, and other subjects. Although he struggled throughout his time in America, Cabeza de Vaca respected the indigenous people for their kindness to him.

Throughout the sixteenth and into the early seventeenth century, other explorers and settlers recorded their encounters with America. Such reports came from other Spaniards, such as Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, who traveled throughout the American Southwest, and Hernán Cortés, who traveled throughout Mexico, ultimately conquering the Aztec empire. Englishmen Arthur Barlowe described his voyage to Roanoke and John Smith wrote of his experiences in Jamestown, as well as other parts of the eastern coast. Frenchmen like Samuel de Champlain played an integral role in France’s claims to land in what is now Canada and the northeast United States, and Robert de La Salle traveled the length of the Mississippi River and claimed the Mississippi River basin for France, naming it Louisiana.

By the seventeenth century, much of North America’s eastern coast was being settled, with new immigrants creating communities or joining existing ones. These settlements fostered new publications, with some of the writing intended for people living in the colonies rather than for those living in Europe. Most of these nonfiction publications focused on issues important for people in these new towns and cities, including histories and religious tracts. One of the earliest and most important works from this period was William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation. A Puritan Separatist, Bradford came to North America on the Mayflower and settled in Plymouth, Massachusetts. His history of the region depicts the community’s experiences from 1621 through the 1640s, and he also explains the religious reasons for the Puritans’ exodus to North America.

John Winthrop, one of the founders and the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company, brought his Puritan beliefs to the colonies in 1630. On his voyage to America, he gave a speech, later published as A Model of Christian Charity, outlining his ideas about building a community based on religious responsibility. Like other Puritans, he believed that God creates roles for each human and that all people play a role in the community, whether as leader or follower, or as rich man or poor. Society, Winthrop argued, requires the cooperation of its members working together. Winthrop also kept a journal detailing his experiences in America, which was published as The History of New England from 1630–1649. After several generations of Puritans established colonies in North America, Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister in Boston, scripted his comprehensive work on the history of religion in New England. Magnalia Christi Americana (1702) tells of the hard work and dedication demonstrated by generations of New England settlers who established communities steeped in a Puritan sensibility.

An original member of the Massachusetts Bay Company like Winthrop, Anne Bradstreet wrote poetry as a child in England and continued in America. In addition to lyric poems such as “A Letter to Her Husband, Absent upon Public Employment,” “The Author to Her Book,” and poems in memory of her father, grandchildren, and others, Bradstreet also wrote a series of “Meditations.” A collection of her work was first published in England in 1650, making Bradstreet the first published poet of the New World. Following Bradstreet’s lead, Michael Wigglesworth, a Puritan minister, became the best-known poet of the age. “The Day of Doom” (1662) inspired a fervent readership, particularly among Puritan readers, due in part to the poem’s graphic descriptions of the day when God returns to judge the wicked:

Mean men lament, great men do rent

their robes and tear their hair:

They do not spare their flesh to tear

through horrible despair.

All kindreds wail, their hearts do fail:

horrour the world doth fill

With weeping eyes, and loud out-cries,

yet knows not how to kill.

(stanza 11)

Such powerful religious language highlights the centrality of religious themes to the literatures of the British colonies. Not surprisingly, many colonists who fled England to escape religious persecution appreciated religious verse.

Although much of the writing from seventeenth-century America focuses on the establishment of colonies and religion in the New World, other publications accentuate the dangers of life in an apparently uncivilized land. On February 10, 1676, Mary Rowlandson, a minister’s wife, was kidnapped along with her three children by members of the Wampanoag. A prisoner for eleven weeks and then ransomed for twenty pounds, Rowlandson records her experiences in A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682). The narrative excited readers, and her religious devotion served as an example for others in duress. Rowlandson’s captivity narrative is the most famous of this genre. Some stories of captivity recount not only captivity’s dangers but also its positive features. In 1755, young Mary Jemison and her family were kidnapped by a group of Shawnee and Frenchmen during the French and Indian War. After many of her family died, Seneca Indians adopted her. Eventually she married a Delaware and, after he died, a Seneca. When Jemison had the opportunity to return to the colonies, she instead stayed and lived out her days among the Seneca. Her experiences were published in 1824 as Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison. The publication of these captivity narratives and of other stories of adventure, such as that of Cabeza de Vaca, started a long series of American adventure literature.

Large books have been written on this subject, and large books will continue to be written on it. But we can offer a few brief generalizations that may be useful.

First, the word “literature”can be used to refer to anything written.The Department of Agriculture will, upon request, send an applicant “literature on canning tomatoes.” People who ask for such material expect it to be clear and informative, but they do not expect it to be interesting in itself. They do not read it for the experience of reading it; they read it only if they are thinking about canning tomatoes.

There is, however, a sort of literature that people do read without expecting a practical payoff. They read the sort of writing that is in An Introduction to Literature because they expect it to hold their interest and to provide pleasure. They may vaguely feel that it will be good for them, but they don’t read it because it will be good for them, any more than they dance because dancing provides healthful exercise. Dancing may indeed be healthful, but that’s not why people dance. They dance because dancing affords a special kind of pleasure.

For similar reasons people watch athletic contests and go to concerts or to the theater.We participate in activities such as these not because we expect some sort of later reward but because we know that the experience of participating is in itself rewarding. Perhaps the best explanation is that the experiences are absorbing—which is to say they take us out of ourselves for a while—and that (especially in the case of concerts, dance performances, and athletic contests) they allow us to appreciate excellence, to admire achievement. Most of us can swim or toss a ball and maybe even hit a ball, but when we go to a swimming meet or to a ball game we see a level of performance that evokes our admiration.

The early achievements of Greek literature are evident in two epic poems, Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey (c. eighth century BCE). The Iliad relates the story of the Trojan War fought between Troy and Greece, focusing primarily on Achilles, the mightiest Greek warrior. Along with powerful descriptions of battles and deaths, the epic contains deep emotional content, particularly in the grief Achilles feels after Hector, the Trojan king’s eldest son, kills his friend Patroclus. Struggling with his loss, Achilles avenges Patroclus’s death by stabbing Hector through the neck with a spear. Hector pleads with him to return his dead body to his family for burial rather than to leave him on the battlefield, but Achilles furiously responds,

(more…)

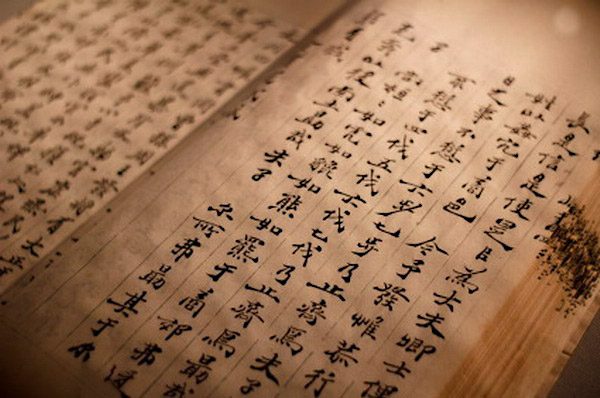

The first great period of Chinese literature came during the Zhou dynasty, which ruled from about 1045 to 221 BCE. The Book of Songs (also known as Classic of Poetry) collects approximately 300 poems whose authors are mostly unknown. These lyric poems focus on a range of subjects including love, friendship, children, sacrifice, war, and admiration for the dynastic rulers. For many years, it was suggested that Confucius compiled an edition of The Book of Songs but no evidence proves his involvement. The poems speak simply yet directly, reflecting the concerns of the people at that time. In a poem celebrating the Duke of Zhou, the speaker proclaims:

Broken were our axes

And chipped our hatchets.

But since the Duke of [Z]hou came to the East

Throughout the kingdoms all is well.

He has shown compassion to us people,

He has greatly helped us.

(de Grazia 40; song 232, lines 1–6)

(more…)