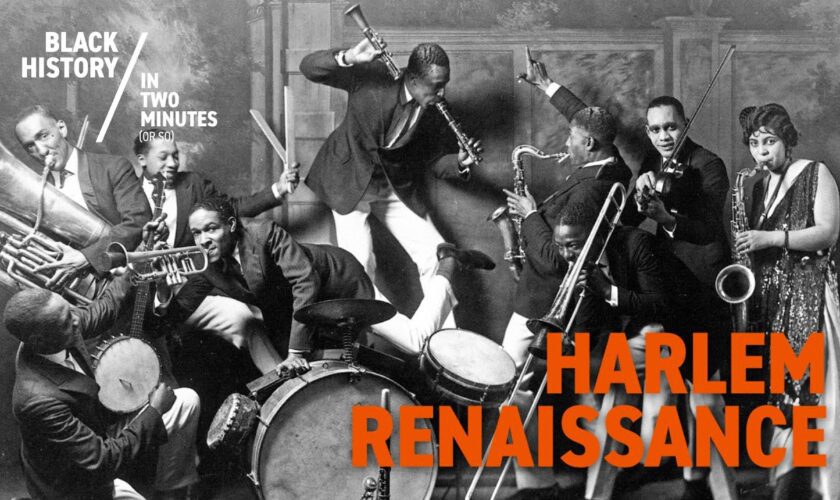

The term normally used to describe the upsurge of black American writing in the 19205 and 19305. Though sometimes seen as a movement, it is better regarded as the more or less contemporary emergence of a number of writers who together make up the first modern generation of black American writers, a generation whose work, while often protesting about dispossession, poverty, and racial prejudice, is most significant for its articulation of a positive sense of black identity and its attempts to promote black consciousness. Harlem, viewed as a cultural matrix for blacks, provided a central focus for the activities of several of the writers who contributed to the Renaissance, or Awakening as it is sometimes also called, but others lived all or most of their lives elsewhere. Although there had been numerous earlier works that gave voice to the predicament of Americans of African descent, among them Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), which is the best-known ‘literary’ example of the genre of slave narrative, Charles W.

Chesnutt’s The Conjure Man (1899), and James Weldon Johnson’s Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man (1912), a work which is sometimes seen as a forerunner of the Awakening, the Renaissance is generally viewed as a major step forward. Figures instrumental in its formation included the sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, best known for his The Souls of Black Folks (1903), who rejected the integrationist approach of his famous contemporary Booker T. Washington, and the Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, whose United Negro Improvement Association promoted an awareness of African origins and the possibility of an actual repatriation to Africa in Harlem in the 19205. Other historical factors which contributed to the growth of a sense of distinctive racial identity and the emergence of an autonomous black literature in the 19205 included the racism from which many black Americans suffered when they served alongside their white compatriots in the First World War, the northward migration of blacks from the rural South, and the difficulties such newcomers experienced in adjusting to urban situations.

The emergence of Du Bois’s magazine The Crisis provided a forum in which black Americans could express their ideas without having to accommodate them to a white readership. When mainstream publishing outlets began to publish black writers shortly afterwards, a readership that was sympathetic to black causes was securely established.

Jessie Redmon Fauset, also an editor of The Crisis, Zora Neale ‘Hurston, and Dorothy *West were notable women figures of the Renaissance. The movement can be seen as having been ushered in by poems such as Claude *McKay’s ‘If We Must Die’ (1919), Countee *Cullen’s ‘I Have a Rendezvous with

Life’, and Langston *Hughes’s The Negro Speaks of Rivers’ (both 1921). Among its most important works are McKay’s Harlem Shadows (1922), Banjo (1929), and Banana Bottom (1933); Jean *Toomer’s Cane (1923); Langston Hughes’s The Weary Blues (192.6) and The Ways of White Folks (1934); Countee Cullen’s Color (1925), Copper Sun (1927), and The Black Christ (1929); Rudolf Fisher’s The Conjure Man Dies (1932); and Arna Bontemps’s Black Thunder (1935)- Varied though these writings are, they illustrate the complexity and richness of black experience and in so doing demonstrate an emancipation from the cultural stereotyping from which blacks had continued to suffer in the Reconstruction period after the Civil War and subsequently.