Although writers living in the area of current-day Iran (the historic Persia) from the sixth through the fourteenth centuries CE wrote in a variety of literary genres, the height of literary artistry was found in their poetry. During the pre-Islamic era (c. 500–620), a rich tradition of oral poetry addressed a range of subjects including love, praise, and sorrow. The

qası–dahs, or odes, are perhaps the most well-known type of Persian poetry. In Al-Shanfara–’s qası–dah “Laˆmıˆyat al-’Arab,” the speaker tells of being rejected by his family and going into the wilds where “a sleek leopard, and a fell hyena with shaggy mane [are] / True comrades” (Lichtenstadter 150; lines 6–7). As an outcast, he is alone, yet achieves a sense of independence with his

… companions three at last: an intrepid soul,

A glittering trenchant blade, a tough bow of ample size,

Loud-twanging, the sides thereof smooth-polished, a handsome bow

Hung down from the shoulder-belt by thongs in a comely wise,

That groans, when the arrow slips away, like a woman crushed

By losses, bereaved of all her children, who wails and cries.

(lines 17–22)

The speaker’s rejection by his family sends him into physical and emotional desolation. His comparison of the sound of his bow to a grieving woman’s sobs indicates his deep pain at living in this place far beyond the world he knows. The poem’s imagery vibrantly depicts the world at that time, a poetic strategy also apparent in “Rain” by Imra’ al-Qays. This speaker describes a rainstorm through a series of vivid similes: rain is compared to the beating wings of a bird, clouds are compared to clothing falling over the earth, and the storm pounding through the trees makes them “look as if headless but covered with veils” (Lichtenstadter 151; line 4). Poets writing in Arabic shared similar concerns to the Persian poets. One of the better known female poets from the era, Al-Khansa–’, wrote “Lament for a Brother,” in which she angrily addresses and personifies death because of her brother’s passing: “What have we done to you, death / that you treat us so, / with always another catch” (Pound, Arabic 33; lines 1–3). Her anger over her brother’s early passing is tempered only by her wish for him to have comfort: “Peace / be upon him and Spring / rains water his tomb” (lines 21–23). These poets create lyrics uniting human passion and artistic skill, meditating on the potential pain of the human condition.

Persian and Arabic literature changed with the birth of Islam and the writing of the Qur’an, which shares Allah’s revelations to Muhammad from 609–632. Written in Arabic, the Qur’an employs many poetic devices that have brought it attention as a literary, as well as a spiritual, work. The Qur’an dramatically shifted the focus of much literature of the period to religious themes. During this era, fiction was largely discouraged, but poetry maintained its prestige. From approximately 750 through 1400, as the larger society adopted Islam as its faith and cultural expectations changed, a new golden age of Persian literature, largely focused on religious content, arose. The Ruba’iyat of Omar Khayyam, composed throughout his lifetime (c. 1048–1131), is a collection of quatrains, four-line poems. Khayyam’s poems are varied, although they consistently evince an appreciation of life, nature, and spirituality. In one poem he writes, “Since no one can Tomorrow guarantee / Enjoy the moment, let your heart be free” (Khayyam 66; poem 15, lines 1–2). Many of his poems express a desire for living for the moment and enjoying life, but these messages reflect his belief that living in the present allows one to connect with the divine. He depicts his passion for life with a variety of images of sensuality and robustness, including references to drinking wine. In the following poem, he connects such images to his religious beliefs:

Deliver me, O Lord, from prayer and plea,

Rid me of self and let me be with THEE:

When sober, good and bad engage my mind;

Let me be drunk—of good and bad be free.

(233; poem 165)

In Khayyam’s poetry, drunkenness is not simply physical intoxication; instead, his plea for drunkenness seeks the elation of union with Allah. This combination of physical and spiritual ecstasy inspires many of his poems.

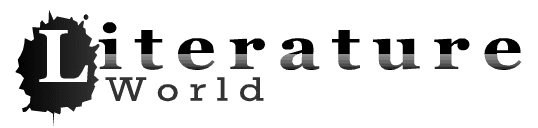

Sufism, a practice of mysticism within Islam, arose during this period, and much Persian poetry reflects this tradition. Among other elements that define Sufism is the belief that one may find Allah and grow close to Him while living in this world, rather than waiting until death. Sufi poets emphasize the need to appreciate life in its present moment and to let go of the distractions of the world to achieve spiritual wholeness. The most famous Sufi poet from this era is Jala–l al-Dı–n Ru–mı– (also spelled Ru´mı´), whose major works include Masnavi, a six-book religious poem combined with brief stories, and Divan-I Shams-I Tabriz, a collection of short lyric poems. In this passage from Masnavi

(c. 1258–1273), Ru–mı– delights in the love of Allah:

Thou art as joy, and we are laughing;

The laughter is the consequence of the joy.

Our every motion every moment testifies,

For it proves the presence of the Everlasting God.

(Rúmí 263; bk. 5, story 8)

The poem depicts a deep pleasure in the simplicity of the connection between the physical world and the spiritual world, recognizing the power of Allah in everyday life.

The lyric poetry of Ha–fiz of Shiraz emerges from the mystic traditions of the Sufis, with his many love poems suggesting passion for both the spiritual and the physical world. Some of his works muse on secular understandings of love, while others express devotion to Allah. In many cases the poems can be read as simultaneously addressing both aspects of life. In his religious poem “Revelation,” he begins, “My soul is the veil of his love, / Mine eye is the glass of his grace” (Arberry 77; lines 1–2). The language conjures images of romance while expressing devout sensibilities. Even as much of his poetry tackles the subject of faith, he also writes sensual poetry. In this passage from “Desire,” Ha–fiz writes:

I cease not from desire till my desire

Is satisfied; or let my mouth attain

My love’s red mouth, or let my soul expire,

Sighed from those lips that sought her lips in vain.

(Arberry 69; lines 1–4)

Hafiz presents the passion of religious ecstasy and physical sensuality. While Ha–fiz, Ru–mı–, and Khayyam are only a few of the many talented poets of this era, they illustrate the mixture of religious and secular themes characterizing much literary art during the centuries after Islam’s birth.

Poetry served as the primary literary form during this period, yet the story collection The Thousand and One Nights is likely its best-known work. Ironically, because its prose resembles spoken Arabic and its stories are fantastical, the work was considered unworthy of serious literary attention in its day. The stories were likely collected over centuries, with the earliest written extant version from the fourteenth century. Perhaps the most famous stories for modern Western audiences detail the exploits of the sailor Sinbad, who travels to magical lands and experiences incredible adventures. The stories themselves are engaging, but the frame story holds the complete work together. King Shahrayar, angry over his wife’s infidelity, kills her. He then marries a new woman each night and murders her the following morning to prevent any possibility of unfaithfulness. Shahrazad volunteers to marry him, with a plan to stop the slaughter. An excellent storyteller, Shahrazad stays up each night narrating a story to Shahrayar, only to stop before a climactic moment as the sun rises in the morning. Because Shahrayar wants to hear each story’s end, he delays her execution for another day, until, after 1,001 nights, he cancels his plans entirely. The variety of Arabic and Persian literature reflects the vast changes occurring in religion and culture during these centuries.